Paul Mertz wrote this very personal and almost poetic text for Roots about one of the icons of Dutch graphic design, Wim Crouwel. About whom, said Mertz, ‘much has been written and much has been said. His authorized biography [Wim Crouwel: Mode en module, 1997], covering the period until his seventieth birthday, is a precision monument. What can you, should you add to this, ten years later? In Roots, on 12 inner pages? You run, you zap through his life.’

Groningen. Willem Hendrik Crouwel. Child. Grandchild. When visiting his opa and oma’s house he often disappears. To neighbor Job Hansen. Who lives in an attic. Where he always paints the same view. The Noorderplantsoen public gardens. In the spirit of De Ploeg. Wim befriends the son and learns from the father. Learns to look, to widen his outlook. ‘The man had a great influence on me.’ Rightly said. Young Crouwel, too, sets himself at the easel. But painting is not his vocation. He loves a good painting though. Most certainly.

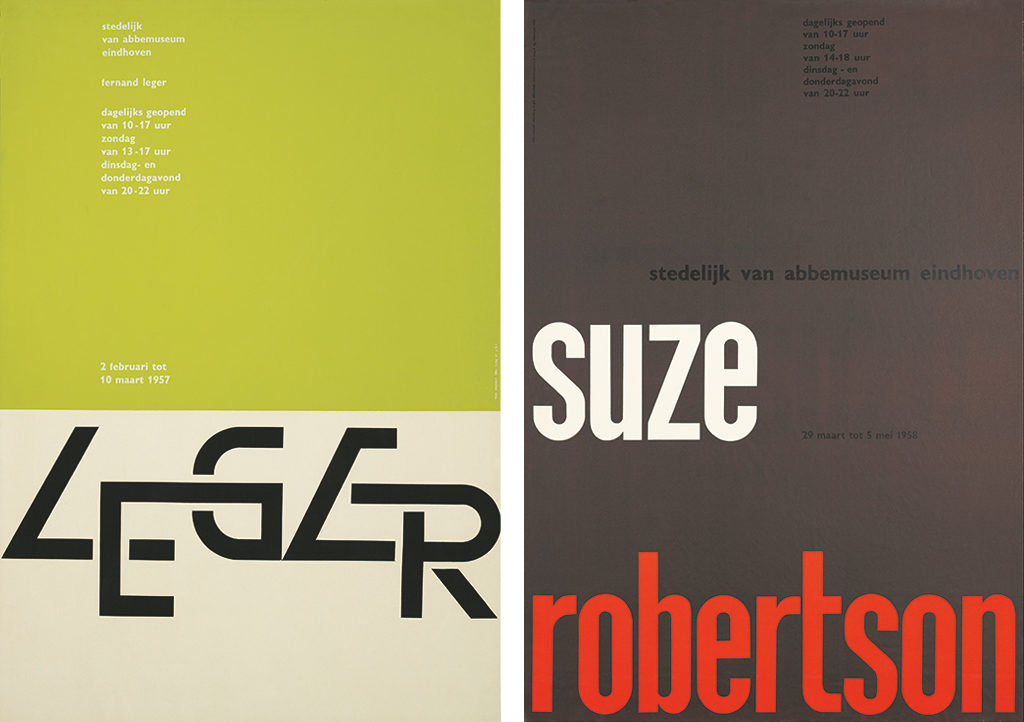

Van Abbemuseum. Director Edy de Wilde hires Wim Crouwel. Fresh. As the museum’s regular designer. Posters, catalogs, a substantial production. Van Abbe keeps up with the pace of the times and doesn’t have a moment’s peace. Crouwel presents his credo. The museum comes first, not the artist. No subjective designs based on the views of the artist whose work is on show. A clear, relevant, consistent system of well-organized and ordered information. No decorations, no popular interpretations. De Wilde, the artists’ friend, hesitates. Then consents. The execution turns out less rigorous than the words professed. Crouwel: ‘Eindhoven was, in hindsight, a period of seeking.’

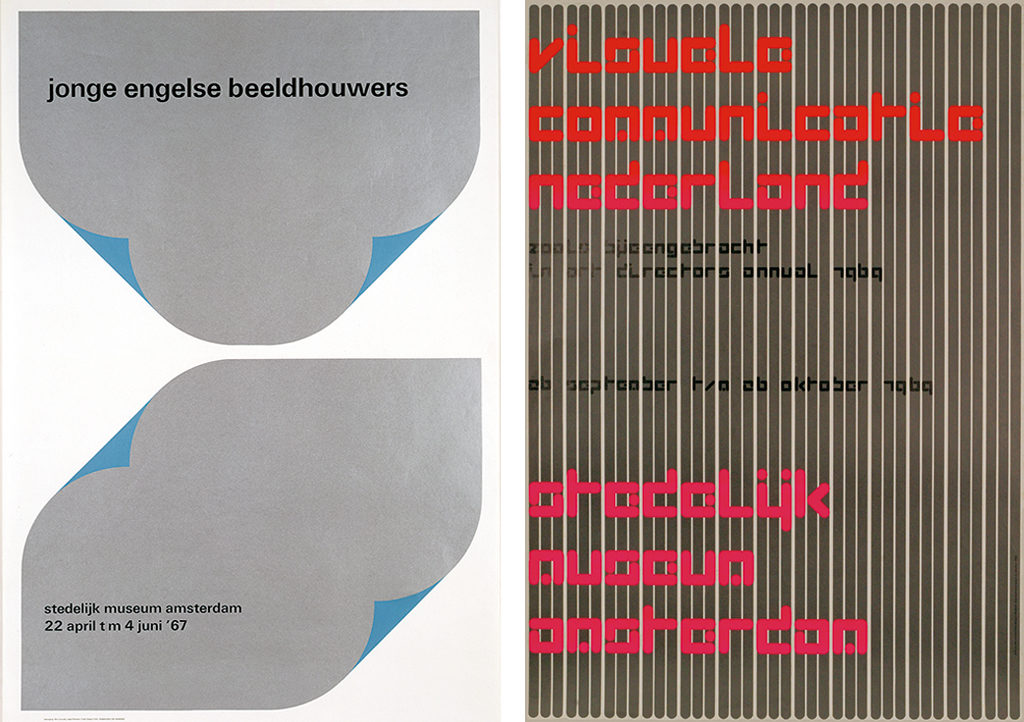

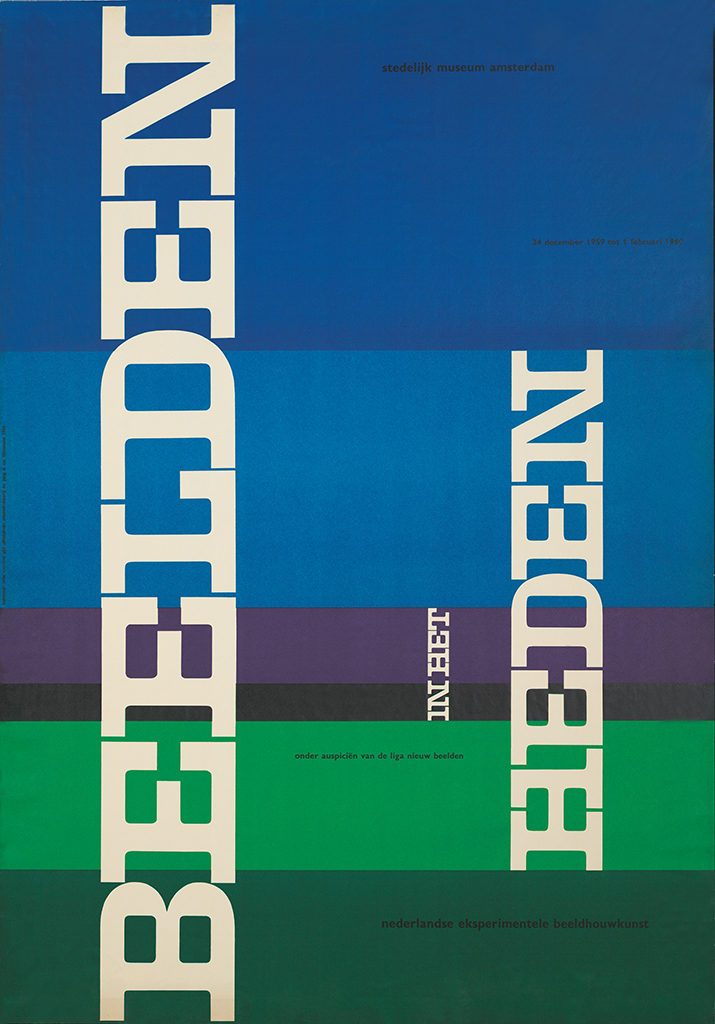

Stedelijk Museum. Director Sandberg is succeeded byDe Wilde. Designer Sandberg is succeeded by Crouwel. What a contrast. The leaving man is a poet. In words, in style, in forms, in imagery. Emotion splashes, from every page. The coming man is altogether different. Rational. An almost Swiss coolness. The relative playfulness of Eindhoven comes to an end. Reins are tightened. As they should. The Stedelijk operates on a much grander scale. More curators, more individual demands. More exhibitions of more artists. Yet the museum must display a prominent oneness.

Stedelijk Museum. ‘De Wilde is the ideal client.’ And things are settled with the curators. Even the cocky one who always knows better and so articulately objects. Indeed: the new style emerges with resolution. Much different from Sandberg’s. Sober, ascetic, documentary, organizing, ordered. The Stedelijk gradually becomes SM. Nevertheless, even here and now, everything is not tied down, caged in stainless steel. Lightness glimmers, from time to time. And, under the influence of others, new and diversified forms of expression come into being. Calendar posters, institutional placards such as ‘Where is Piet Mondrian? Always at the Stedelijk’. Crouwel seizes them swiftly and skillfully.

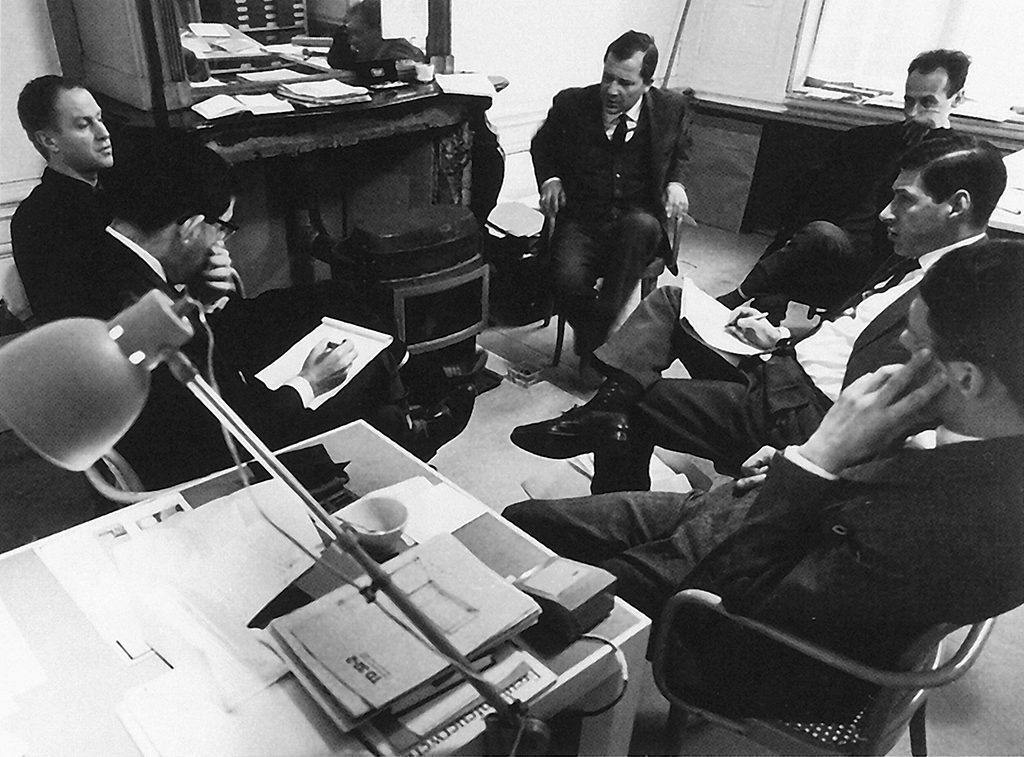

TD. Total Design. A little presumptuous, that name, for the industrial design part doesn’t bloom easily. But no design studio created a position in the market so soon, so convinced and so convincing. So much talent on board. That doesn’t always make it easy. Characters do clash. Too. For Crouwel – designer, philosopher, figure head, director – they are often a handful. Still, a stream of outstanding designs leaves Herengracht 567. Legions of logos. For outstanding clients. Bed manufacturer Auping, the city of Groningen, the city of Rotterdam, the World Trade Center. Not to forget Crouwel’s postage stamp designs and the phone book. Crouwel remains at TD for twenty-two years.

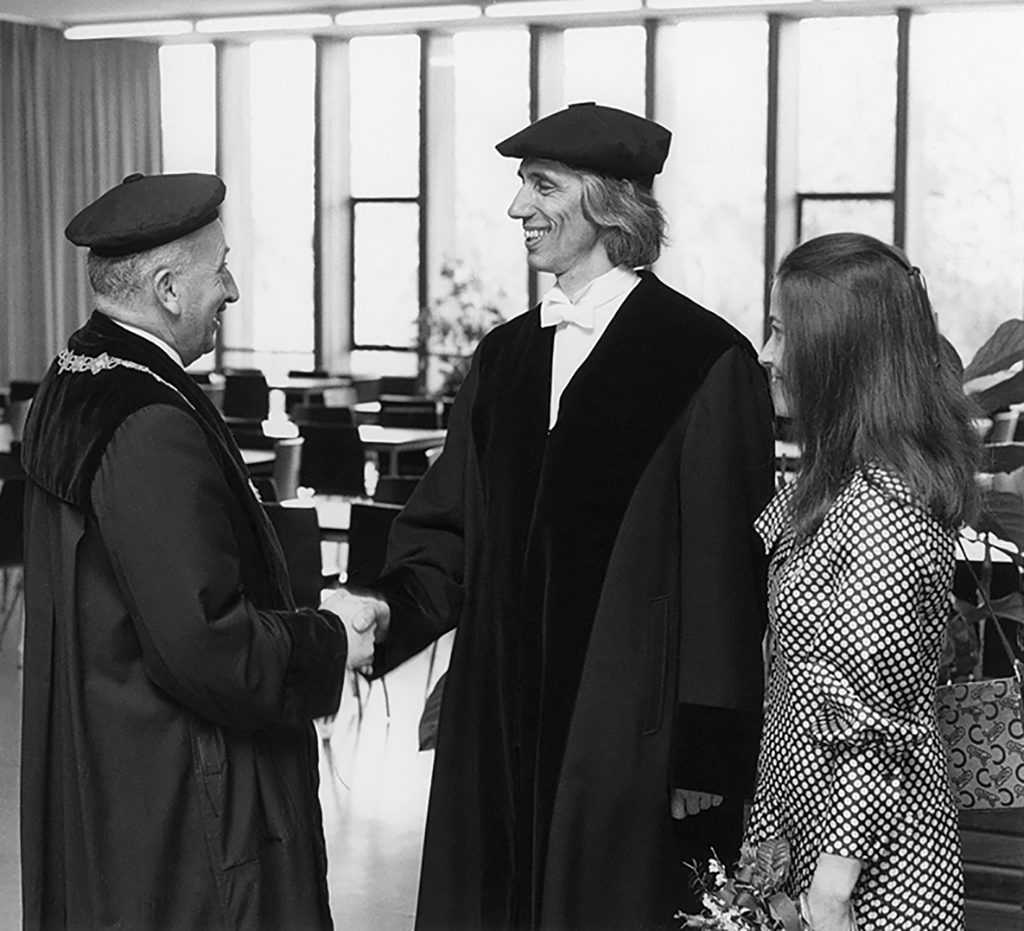

Delft. TH, Technische Hogeschool (Technical University). Crouwel starts teaching at the Industrial Design department. While continuing full-time at TD. He becomes a lecturer, then an associate professor. They won’t let him go. He becomes a professor, the department’s dean. Industrial Design is still the name of the game. After Delft: Rotterdam. Erasmus University: associate professor for Art and Culture. The title is fitting: Crouwel is scholarly, finds his way fast whatever the subject, is a master of organizing the facts, expresses gutsy opinions, articulates his thoughts in a resonant and tangible way.

Boijmans. Change of the guard. De Wilde leaves SM, Wim Beeren takes over. Which means Boijmans needs a new director. Hard to find. Until Joop Linthorst, city councilor, suggests Crouwel to apply for the job. But can he? As a member of the museum’s advisory board. Crouwel: ‘I didn’t step forward, I was asked.’ He becomes the new Boijmans director. Isn’t that a dreadful transition? After a long career as a designer, now to manage a museum? Not so much. Crouwel knows what leadership means, has gained experience at TD and TH. He already knows Boijmans inside and out. Staff, strengths, weaknesses. An advantage.

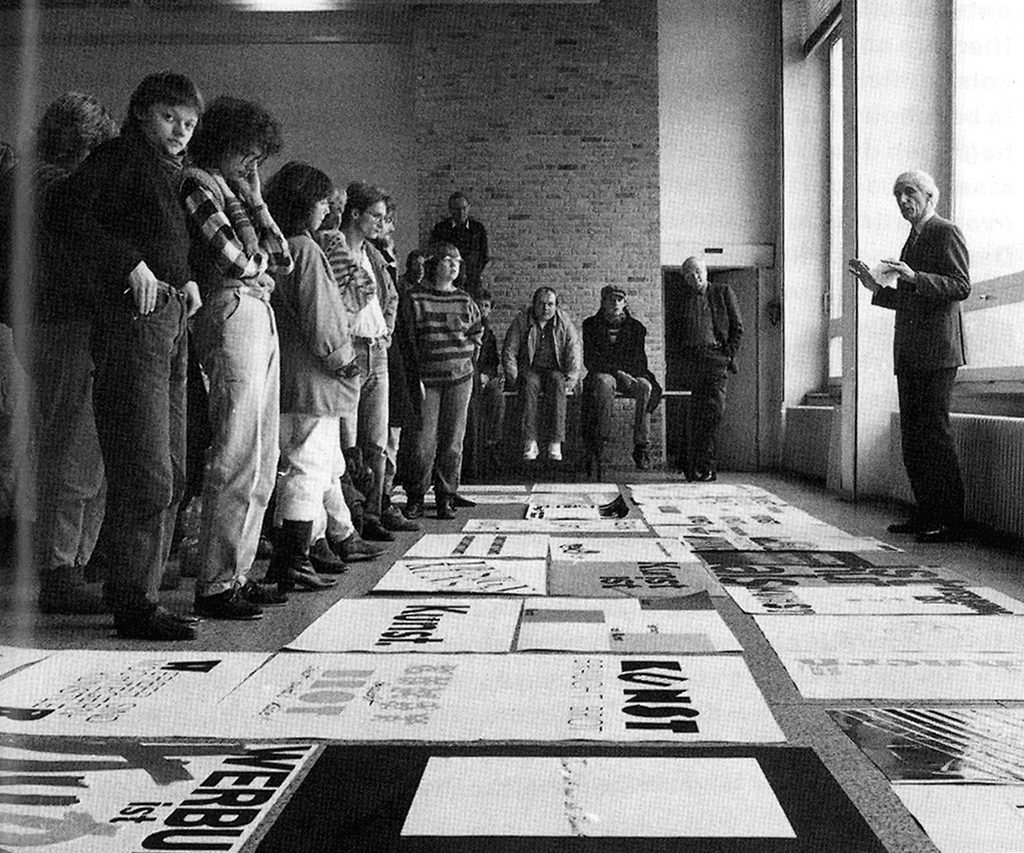

Boijmans. Crouwel is no Sandberg. He is not a committed DIY-er. He engages a young British design duo, 8vo (octavo). They get a free hand. On the condition they keep the Futura. Crouwel concentrates on content. The balance between old art and new art. Siloed museum disciplines. New exhibition spaces. A high-end museum store. The acquisition policy, which includes design. A sensational commission for Harald Szeemann: mix our collections into exhibitions. Crouwel, also, inspires the curators, brings them together, breaks through long-existing walls. Permanently. Equally spectacular is the exhibitionVerboden stad [Forbidden City]. He can’t let this opportunity pass him by, decides to design the exhibition himself.

Typefaces. Wim Crouwel is a typographer pur sang. With likes and dislikes. And his very own alphabet: new alphabet.

Futura and Crouwel were both born in 1928. No, rather no Helvetica.

Gill was acceptable for Van Abbe. Its form, dimensioning and gradations are winning.

Univers for SM. A beauty, clear, cognitive, economical.

The Swiss Akzidenz Grotesk is not available, in the Netherlands. Alas.

Garamond. A beauty indeed, but cannot be applied everywhere.

If a Roman type is necessary, then Bembo.

new alphabet, meanwhile, is made for this century.

2D 3D. The flat surface is Crouwel’s love. His graphic designs bear testimony. Depth is taboo. So is perspective. At most a defined space may be suggested. Only by using color and typography. Nevertheless, Crouwel’s career starts as builder of exhibitions. For Enderberg. The third dimension has a real presence in his oeuvre. Emphatic, through all the years, but under-exposed. Even his contribution to the Dutch pavilion in Osaka. Crouwel said recently: ‘3D is delightful, it is my passion. I do it together with my youngest son Remco.Because of him I can still do it. He can handle high resolutions, heavy files. And I just love it.’

Van Gogh. Who and what keeps Wim Crouwel from being bored? The Rembrandt Society, celebrating 125 years. With a memorable exhibition at the Van Gogh. Showing, that’s right, 125 great loves. Remarkable works, Dutch and foreign, bought with support from the Society. For repatriation and preservation. Peter Hecht is the visiting curator and writes a book that reads like a novel. Crouwel designs the exhibition. No easy job, in that circular pavilion. Paintings don’t bend, don’t give way. ‘So I install a square box. I pay much attention to combinations, sight lines and vantage points. And to frames. You cannot find them in catalogs or on the intranet. But they can destroy your design.’

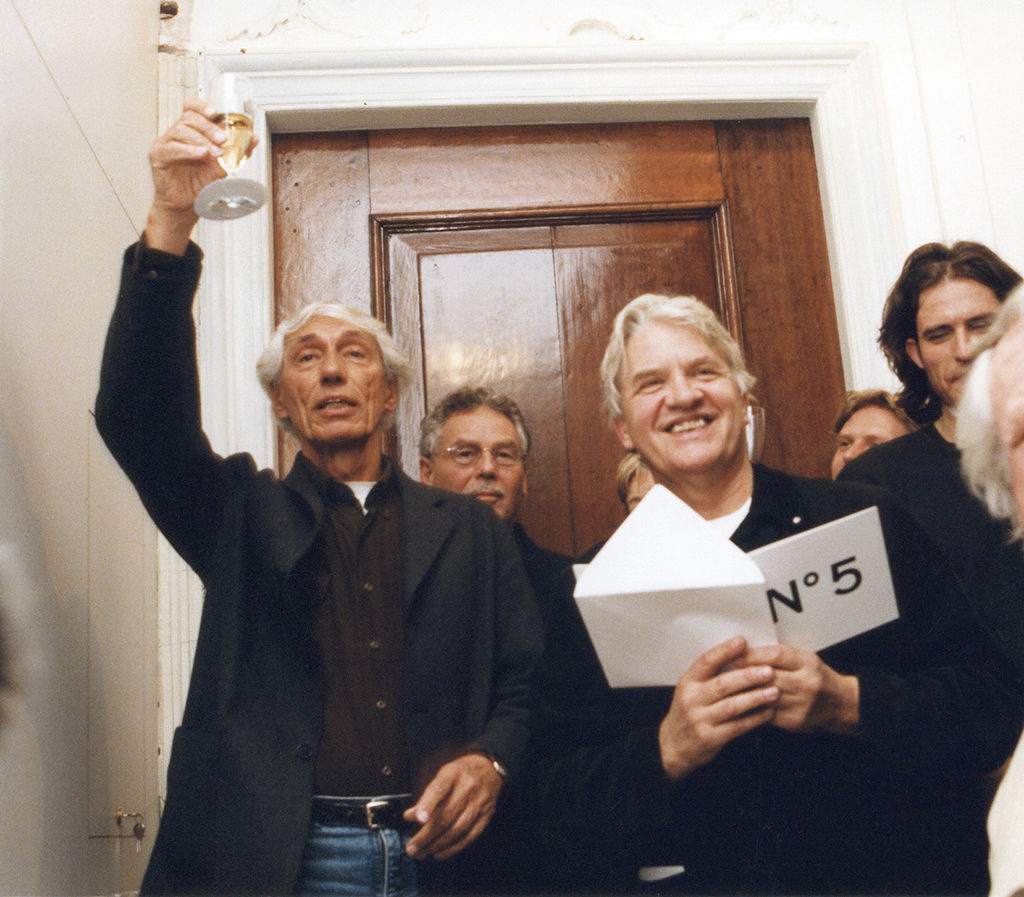

Much milder. Time flies,but certainly not centuries ago Wim Crouwel declares Anthon Beeke’s new studio at Keizersgracht to be officially open. He stands at the top of the stairs. Looks down, addresses the crowd. ‘This was not deliberate, honestly. No Olympus, it just happened this way.’ Either way, it was a historic moment. Crouwel – for many the stern, strict, rigid designer – intimates, all but submits that he might have been a little too uncompromising. In his principles. Over the years. Incidentally, he is not unsettled. Not in the least. He delivers the news in his very own way. Eloquent, charming, courteous, melodious. With a laugh that is simultaneously a smile. Such sincerity is not given to everyone.

Wim Crouwel

born on 21 November 1928, Groningen

died on 19 September 2019, Amsterdam

Author of the original text: Paul Mertz, November 2008

English translation and editing: Ton Haak

Final editing: Sybrand Zijlstra

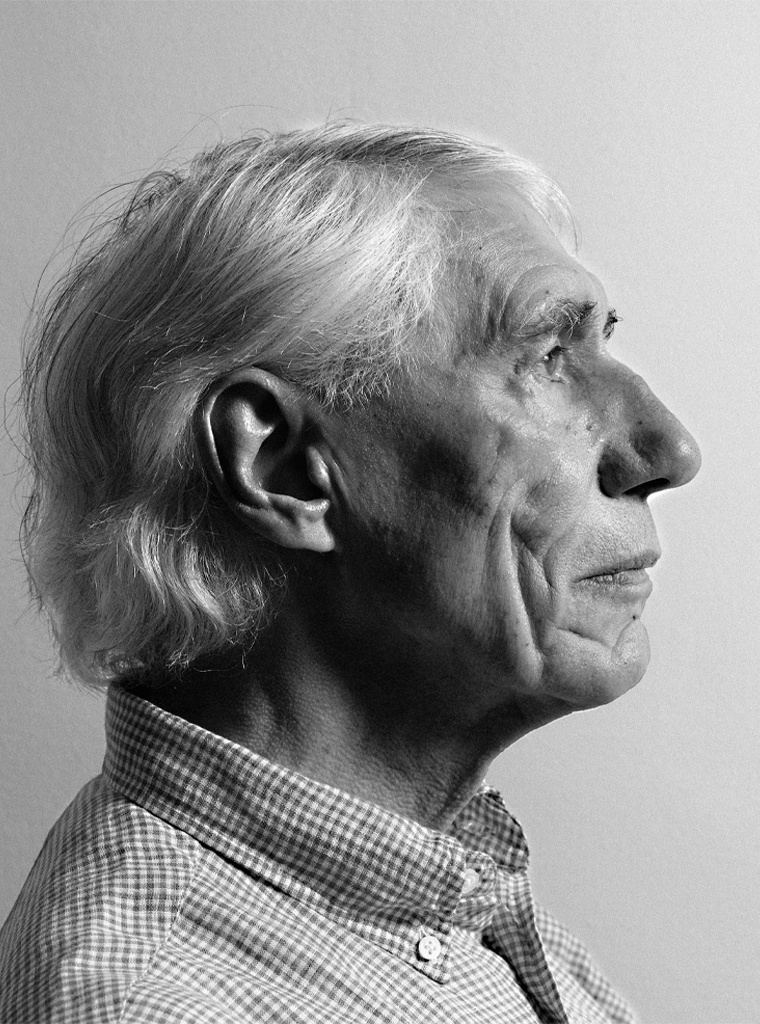

Portrait photo: Aatjan Renders